Accuracy:

Clock accuracy is largely determined by how well we can characterize the electromagnetic environment and the sensitivity of the atomic transition to these disturbances. In addition, motion of the atom introduces relativistic corrections. The most fundamental influences on clock accuracy for an ion-based clock are:

Stability:

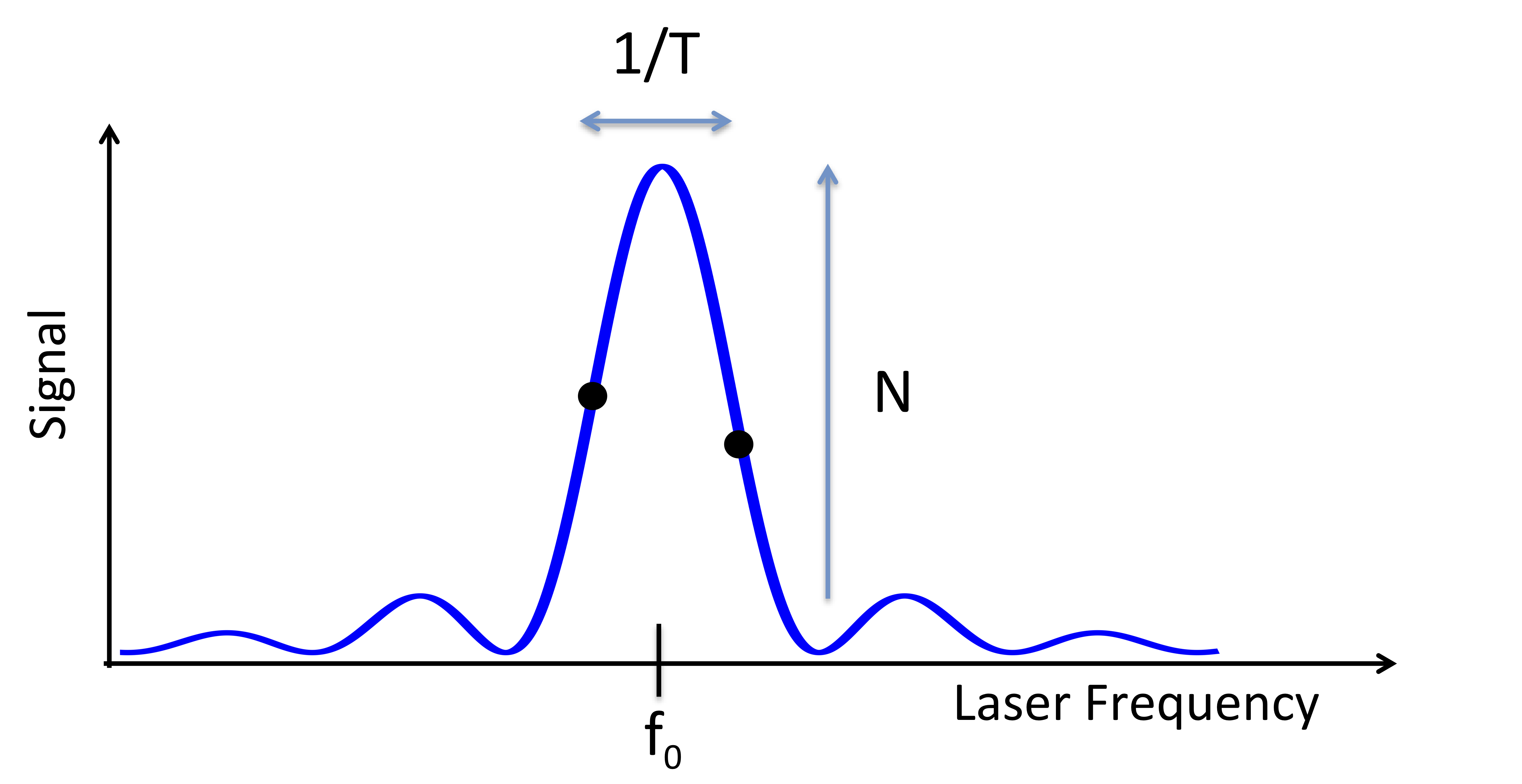

Rabi spectroscopy is a common method for probing or interrogating an atomic transition: the laser drives the atomic transition for a time T and then population in the excited state is measured. The resulting frequency dependent signal is shown here for assuming the laser intensity is such that population transfer is a maximum when the laser is on resonance. The signal has a height determined by the number of atoms, N, and a width inversely proportional to T.

In clock operation, the atom is probed either side of

the resonance and the difference in the two signals is used

to derive an error signal from which to correct the laser

frequency. At the half maximum point an atom has a 50%

chance of being found in the excited state and hence the

error signal has a projection noise of  ,

resulting a frequency variation of

,

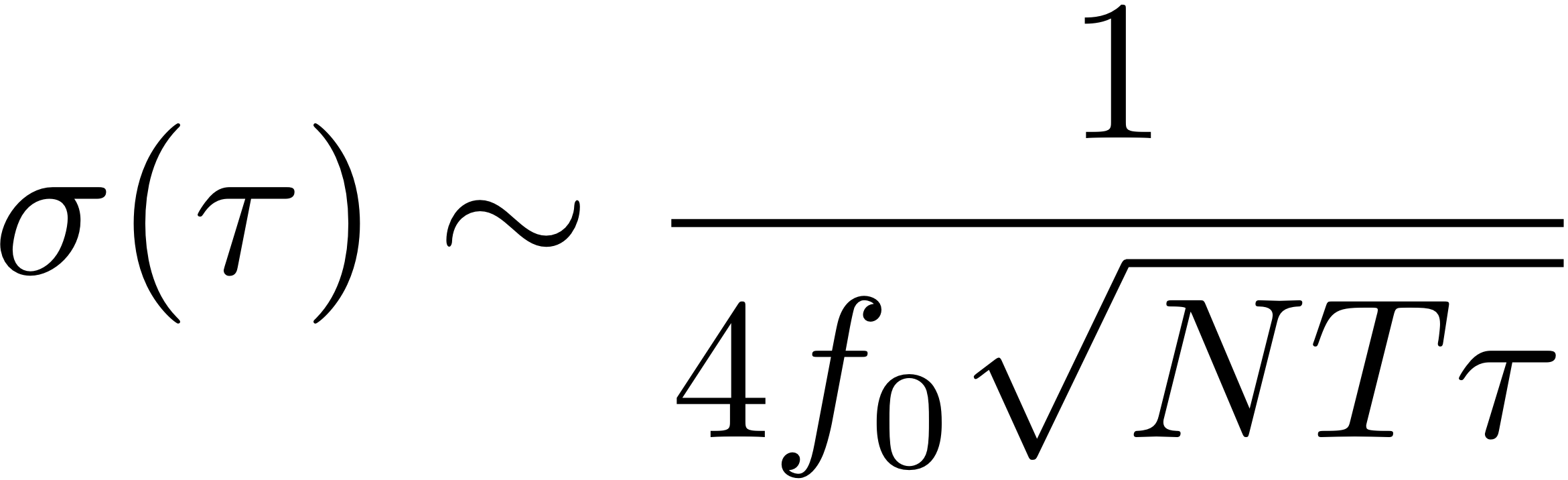

resulting a frequency variation of  . In a

time τ we can ideally make τ/T measurements resulting

in a fractional instability

. In a

time τ we can ideally make τ/T measurements resulting

in a fractional instability

Other interrogation techniques, such as Ramsey spectroscopy, yield a similar result. This expression motivates the use of higher clock frequencies, larger numbers of atoms and longer interrogation times.

The interrogation time T is limited by the transition lifetime, environmental noise shifting the atomic transition, or the laser coherence time. We typically choose transitions that have long lifetimes and low sensitivity to external noise so that, in practice, the limitation is due to laser technology.